Smishing is not a new concept. According to the Macmillan Dictionary, the term was coined in 2006 when David Rayhawk used it in a McAfee blog.

Meaning SMS phishing, smishing refers to scams perpetrated by text messages, with our mobile phones being used as the attack platform from which threat actors will attempt to steal personal details such as a credit card number.

So, why are we talking about it today? In large part because smishing attacks have spiked of late, rising 328% in 2020 alone, and they are succeeding. According to the FBI’s 2020 cybercrime complaint report, phishing-based techniques such as smishing cost over $54m in losses last year.

Indeed, many smishing campaigns are as easy to spot as fraudulent activities. Yet such figures suggest a significant and growing problem. This is because much of the challenge today lies not in the increased volume of smishing attempts but the ever-increasing complexity of such attacks.

In April 2020, Menlo’s threat research team saw a spike in mobile users being targeted with smishing messages in what appeared to be a highly organized and sophisticated spam campaign.

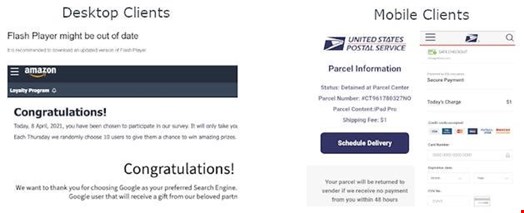

This particular campaign impersonated the United States Postal Service (USPS), UPS and FedEx, the content of these text messages being related to fake shipment updates. The threat actors also sent texts promoting fake Amazon loyalty program rewards. The former were used to target mobile clients, while the latter were targeted at desktop clients.

In each case, users are prompted to enter their credit card details alongside other personal information.

The Menlo Labs team observed the campaign to be device agnostic, the perpetrators having leveraged redirection mechanisms to create different landing pages depending on the client browser and device. The landing pages that are generated when a potential victim opens a link are only viewable once, a reload of that specific link resulting in an HTTP 404 (page not found) error.

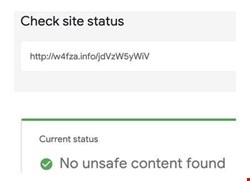

These short URL lifespans are typical of smishing attacks. The vast majority of these were categorized as ‘Unknown’ by popular URL categorization providers on sampling the initial URL domains.

While malicious URLs with longer lifespans may be flagged as malicious by AV vendors, new URLs with shorter lifespans bypass this problem. It simply takes more time for URL categorization and detection vendors to catch up.

This delay is described as ‘green to red’. A short-lived URL may be categorized as benign or unknown when a user clicks on a link shortly after the smishing text is sent, only to become categorized as malicious or spam later – likely when the webpage begins to receive an HTTP 404 error.

The statistics speak for themselves. By the end of April 2021, just 19% of the initial URL domains had been flagged as malicious.

We examined Google Safe Browsing for its detection capabilities, finding it to have a very poor detection ratio for both the initial URLs and landing page URLs. We found that five landing pages and five initial URLs had not been flagged as unsafe through random sampling.

While this campaign demonstrates the growing sophistication of smishing attempts, it is just one example of numerous campaigns that will continue to advance during the coming years.

Beyond such techniques, smishing attacks can equally steal user information using fake two-factor authentication messages and often use local numbers to lure potential victims into carefully cultivated traps.

The question is, what’s the solution?

The challenge is that while individuals and companies alike will keep security front of mind on desktop activities, this is often an afterthought for mobiles. To help combat smishing attacks, similar attitudes and steps need to be taken.

Mobile browser isolation is one such solution that can transform mobile security. It’s a technology that’s been specifically designed not just to combat but eliminate the threat of smishing, phishing and other malware attacks when users unknowingly put themselves in vulnerable positions when using their mobile devices.

Smishing is not going away. To reiterate, such attacks increased 328% in 2020 alone. Given such alarming numbers, it has never been more important to be fully protected.