The DMARC email standard is receiving increased awareness following the October 16, 2017 issuance of Binding Operational Directive BOD-18-01 by the Department of Homeland Security. BOD 18-01 mandates U.S. Government (USG) adoption of DMARC. BOD 18-01 states:

Sender Policy Framework (SPF) and Domain Keys Identified Mail (DKIM) allow a sending domain to effectively "watermark" their emails, making unauthorized emails (e.g., spam, phishing email) easy to detect. When an email is received that does not pass an agency's posted SPF/DKIM rules, Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting & Conformance (DMARC) tells a recipient what the domain owner would like done with the message.

Setting a DMARC policy of "reject" provides the strongest protection against spoofed email, ensuring that unauthenticated messages are rejected at the mail server, even before delivery. Additionally, DMARC reports provide a mechanism for an agency to be made aware of the source of an apparent forgery, information that they would not normally receive otherwise. Multiple recipients can be defined for the receipt of DMARC reports.

Sounds great! Will DMARC actually make email more secure? The answer to that question requires that one look beyond the defensive measures to consider the responses which are available to threat actors.

What measures are available to threat actors in response to DMARC? The answer to that question is driven by the threat actors’ objectives in the email adversarial engagement. What are the objectives of threat actors when they use spam and phishing? BOD 18-01 observes that spam and phishing are problems in which users “fall victim to a phishing email that appears to come from a government-owned system.”

Buried within the phrase “appears to come from a government-owned system” is DMARC’s Achilles’ heel. Appears to whom? DMARC focuses on how email appears to systems. Threat actors focus on how email appears to users. Thus, the problem stated in BOD 18-01 should be restated in terms of the threat actors’ objectives: Users fall victim to email that appears, as perceived by users, to come from a government owned system.

When DMARC is processing emails at the receiving mail server, DMARC IS NOT preventing threat actors’ email from being perceived by users as coming from government-owned servers. Quoting section 2.4 of RFC7489, the DMARC specification:

DMARC does not attempt to solve all problems with spoofed or otherwise fraudulent email. In particular, it does not address the use of visually similar domain names ("cousin domains") or abuse of the RFC5322.From human-readable <display-name>.

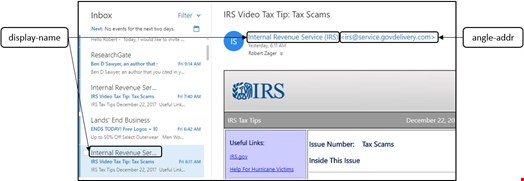

RF5322 section 3.4 and following define the two email address fields which are generally displayed to users. These fields are display-name and the angle-addr. The display-name is a text phrase and the angle-addr is an email address. Within the angle-addr is the domain that purports to be the email sending domain.

This is DMARC’s Achilles’ heel -- users perceive email differently than servers perceive email. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate common deceptive email tactics. The IRS has adopted DMARC and uses a third-party service (govdelivery.com) to send IRS email. Figure 1 shows the familiar Outlook inbox, with focus on the last email. The email in focus is a real IRS email:

Figure 2 shows the same inbox with focus on the email that is second from the top. This email also uses the display-name “Internal Revenue Service” and it passes DMARC. But it is not from the IRS or any USG agency:

Figure 2 is a simulated phishing email. Why didn’t DMARC stop this attack?

DMARC gives the USG control over USG domains, in this case “govdelivery.com.” This solves the problem of unauthorized senders purporting to send email from the controlled domain.

But solving this problem does not stop users from being deceived into errors of perception. The DMARC standard itself explains in sections 2.4 and 12.4 that DMARC does not stop threat actors from using deceptive display names or angle-addrs. The simulated phishing attack leveraged both techniques with the deceptive display-name “Internal Revenue Service (IRS)” and the deceptive angle-addr “irs@service.usgovdelivery.com."

The domain “usgovdelivery.com” exemplifies the cousin domain problem in which the threat actor selects a domain that is consistent with the recipient’s expectations. Cousin domains do not have to be derived from the controlled domain. For example, Russian banks were deceived by emails from the domain “fincert.net”, a domain that a person might associate with FinCert, the Russian bank regulator. FinCert’s actual email domain is “cbr.ru”. Although DMARC does little to disrupt email-based deception, it is possible to fight the human deception problems that DMARC does not address.

DMARC does not stop phishers from displaying deceptive sender information and it does not assist users in avoiding deception. Assertions such as those of U.S. Senator Wyden that DMARC “would make it significantly harder for fraudsters and foreign governments to impersonate federal agencies” overstate the efficacy of DMARC. In fact, threat actors deemphasized the techniques stopped by DMARC long ago.

Phishing is an adversarial engagement in which technically proficient threat actors use psychological manipulation to deceive users into taking compromising actions. DMARC offers significant improvements in email authentication.

However, DMARC will make little, if any, difference in improving email security respecting phishing because DMARC inadequately addresses both the technical proficiency of dedicated threat actors and their tools of psychological manipulation.