Cybersecurity and GRC capabilities are built upon what we call 'The Golden Triangle,' a framework comprising balance between People-Process-Technology. When we evaluate risk and design our control structures, we align them to this framework. The beauty is in the balance between the three.

While our control systems and frameworks focus heavily on measuring the effectiveness of our processes and technologies, less is done on measuring the effectiveness of our people controls… our human controls.

We Are Out of Balance

Humans are and have always been a top vector for attack against digital systems as we are the most crucial control and least effective. According to the 2022 Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report, 82% of all breaches involved a human element. This included stolen credentials, social engineering attacks, misuse or human error.

The human mind is highly susceptible to being psychologically exploited, especially when under stress. This same stressed human mind is expected to perform a complex set of activities, consistently, at the near perfection and breakneck speed necessary to protect and defend against today’s attacks.

Our human controls are breaking, and we are ill-prepared as a security and GRC workforce to operate in a world where our digital, physical and biological ecosystems are colliding.

So, Where is the Breakdown?

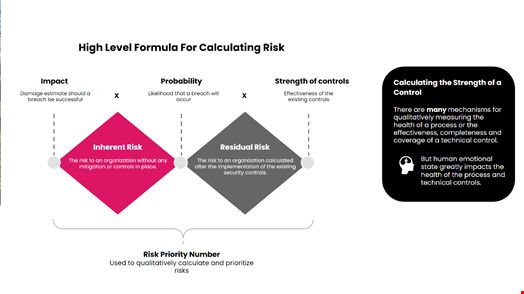

In an information security management system, humans are users, and we are controls. Yet, current risk management models fail to adequately account for the state of the human condition when calculating the strength of a security control.

We hypothesize that risk models are failing to pick up severe risks because we do not effectively measure the strength of the human control, and as a result, the calculation for the strength of a security control is off.

This may result in issues such as:

- Human risks are not detected, and as a result, controls may be ineffective or non-existent.

- An inaccurate list of prioritized risks.

- Architectural impacts to the enterprise security system. We build systems based on controls that are converted into requirements. Whole architectures can change based on a single requirement. Failure to capture the health of the human control means potential for architectural defects in your system or, even worse, the wrong architecture.

In order to better understand how to approach measuring the strength of a human control, we need to understand the systems that govern and influence our behaviors and how they react when the environment is not optimal. It means understanding stress and how it shapes our decision-making, and how the dynamic between emotion and our cognitive functioning impacts that decision-making.

Understanding Stress

Stress is our body’s mechanism of reacting to a condition such as a threat, challenge or physical and psychological barrier. It is an event that may disrupt the equilibrium between ourselves and our environment. Stress is a critical psychobiological mechanism that enables us to quickly and effectively respond to danger and threats.

Stress in Cybersecurity and GRC Professionals

- Stress makes a big difference when it comes to staff retention; 45% of respondents cite high work stress levels as the reason they leave a company, according to ISACA's State of Cybersecurity 2022: Global Update on Workforce Efforts, Resources, and Cyberoperations Report

- 51% of respondents cited work as the greatest source of stress, anxiety and disturbed sleep, according to the Chartered Institute of Information Security's The Security Profession 2020-2021 study.

Cybersecurity and GRC-related positions are fast-paced, high pressure, and require rapid acquisition, interpretation, application and adaptation of complex learning content. We are primary human controls for a security system. Yet half of the security workforce suffers from stress, anxiety and a lack of sleep.

While stress is critical to human survival – it can help raise our defense against danger – long-term chronic stress can have devastating effects.

We have been studying our biological and neurological responses to stress for years, and recent research calls into question our popular beliefs around stress and the answers residing in one of the body’s critical signaling systems, hormones.

Hormones Involved in Stress

Hormones are a class of signaling molecules – the body’s chemical messengers enabling disparate parts of the body to signal and communicate. Hormones help to regulate our physiology, emotions, cognition and social behavior. While they are not the only reason we experience emotion, they contribute significantly.

According to Psychology Today, "Behavior and internal states exert effects on hormone levels via the brain; hormones, in turn, impact mood, memory, and a number of other cognitive and emotional functions. Hence, experiences interpreted by our brains as stressful increase our production of cortisol, oxytocin, progesterone, and other hormones; these hormones, in turn, exert actions on our brains that affect:

- Our ability to make new associations and retrieve older memories,

- Our subjective feelings of negative affect and emotional arousal,

- Perhaps even our propensities to compete with, spend time with, and trust other people."

As humans, our reactions to stress are governed by our hormones. During times of stress, our body produces our ‘fight or flight’ hormones, such as adrenaline, and releases the hormone cortisol soon after, enabling our bodies to stay on high alert, which in turn influences memory formation, ensuring that we are likely to remember that specific threat.

In fact, the plasma levels of hormones such as cortisol can increase by 2-5 times during stress.

However, during stress, we also increase our production of the most beautiful hormone, oxytocin. Oxytocin is the hormone that floods a mother’s body after birth to establish the bond between mother and child. Oxytocin makes us more generous, trusting and ready to bond. Empathy is most closely linked to oxytocin.

The Best and the Worst of Times

In the article, The two faces of oxytocin: Why does the 'tend and befriend' hormone come into play at the best and worst of times?, social psychologist Shelley E. Taylor, Ph.D., stated that the stress-triggered appearance of oxytocin might produce physiological changes that actually encourage people to seek contact with others. When faced with a perceived threat, humans will tend to their young and

‘befriend’ others in their social group for connection and support. Understanding what drives a ‘fight or flight’ vs. a ‘tend and befriend’ is crucial as we will soon discover that our hormonal response to a stressor can give insights into the strength of human control.

For example, attackers, whether by design or by accident, use as their mechanism of attack a weaponized version of empathy, meaning they measure and understand your emotional state and leverage that understanding to manipulate you into a particular action.

"Attackers, whether by design or by accident, use as their mechanism of attack a weaponized version of empathy"

A Correlation Between Stress and Cybersecurity Practices

According to the study, Examining the Link Between Stress Level and Cybersecurity Practices of Hospital Staff in Indonesia, our stress levels play a significant role in predicting our reactions to specific cybersecurity practices. The activities most likely to be impacted by stress were:

- Clicking on a link in an email from an unknown sender

- Failing to prevent colleagues from seeing patients’ information on social media

- Ignoring colleagues practicing bad information security practices

- The creation of weak passwords

This study and others would indicate that stress impacts our decision-making processes by transitioning from goal-directed actions (decisioning based on potential outcomes of future actions) to habit-based decisioning (a reflexive response based on past reinforcement such as prior experiences or ‘gut reactions’).

By understanding the nature of a user’s current mental state, an attacker can trigger specific hormones, trigger a reflexive response and increase the likelihood they execute activities such as clicking on a link.

Cybersecurity and GRC control specialists will need to design controls with the understanding that in a stressed state, humans may lean into a ‘tend and befriend’ reaction, leading them to ignore a colleague violating a security policy.

Understanding the Relationship Between Stress and Empathy

The first step in designing stronger human controls is understanding humans. Empathy is a human’s ability to perceive, share and appropriately respond to the emotional experience of another.

Empathy comprises two mental processes:

- Cognitive empathy. This is our ability to interpret and understand what another person feels. For example, analyzing a person’s facial or body reactions provide insights into a person’s feelings and emotions – their psychological perspectives. This also includes a form of empathy where the individual deliberately manipulates their perspective-taking to actualize a specific goal. Attackers use cognitive empathy and weaponize it.

- Affective empathy. Also called emotional empathy, affective empathy is the ability of a human to share in the experience of pain – to co-experience the same emotion. Emotional empathy inspires compassion. Attackers may leverage a user’s affective empathy to manipulate them to take a specific action. Affective empathy may be triggered if a coworker fails to report a colleague for violating a security policy because they worry that the coworker may be fired.

Understanding the difference between the two is critical. For example, a study published in an Israeli science journal found that “stress-prone people were good at cognitive empathy – in other words, accurately identifying inner states based on outer clues. But there's a critical caveat for the purposes of our discussion: They weren't as good at ‘affective empathy.’ That's a science-y way of saying that they could recognize an emotion, but they weren’t necessarily feeling it themselves.”

ISACA’s State of Cybersecurity 2022: Global Update on Workforce Efforts, Resources, and Cyberoperations Report identified the least-valued soft skill in the cybersecurity industry was empathy (13%). Furthermore, Businessolver's 2021 State of Workplace Empathy study found that 68% of CEOs say they fear they will be less respected if they show empathy in the workplace, up an astonishing 31 points from 2020.

One can undoubtedly infer that, as an industry, we appear to have a gap in our affective empathy.

We are stressed, and that stress marshals our biological resources to survive an imminent threat by flooding our bodies with hormones that enable us to hyperfocus our attention on the specific threat.

While this enhances our cognitive empathy, it is at the expense of our affective empathy. By “protecting ourselves” from being perceived as too emotional, we are disengaging from a part of our emotions necessary to protect and defend our users, our workforce and ourselves.

Unfortunately, attackers are impressive in their ability to exploit the weaknesses in our adaptive empathy mental processes.

Human reactions to stress are complex, and our level of empathy can be a guide to how we might react to particular stressors and give insights into our human control, strength and resiliency.

Maintaining Control Across Biological, Physical and Digital Boundaries

Our worlds and even our bodies are all hyper-instrumented and connected. We will be required to work in, protect and defend environments that are under constant change through augmented and fully virtualized experiences.

It’s a new world. We are pioneers. We’ve never been down some of these roads. To thrive in these new and emerging worlds, our human controls will need the ability to rapidly adapt to change with a near real-time acquisition and application of new skills. This includes strengthening our internal empathy networks, including our weaknesses in affective empathy.

To accomplish this, we need to experiment and innovate, and that requires operating in a world where we, as world builders, control the ecosystem.

How Metaverses Can Help Improve Risk Models

Metaverses provide us with the opportunity to create, at scale, purpose-built universes that enable our workforce to acquire and apply new skills rapidly.

The cybersecurity industry will become world builders, and as designers, we will build entire ecosystems with consideration for the emotional health of the user.

Metaverses combine aspects of the physical and digital worlds with our biological systems. The immersive nature of virtual reality (VR), combined with haptic feedback, can modulate and thus amplify the physiological, neurological and psychological impacts on the human. It is in these newly built intelligent worlds that we can create psychologically and neurologically healthier learning environments for our acquisition, and application of, new skills.

All human-centered design starts with empathy, and we propose using thinking models to identify specific mechanisms to capture the emotional health of our workers at different stages of their learning and operational journeys.

At GRCIE.org (GRC for Intelligent Ecosystems, pronounced Gracie), we train junior cybersecurity and GRC analysts in VR in our custom-designed metaverses. We propose building empathy-based measurement systems into our VR-based learning environments and ultimately into VR-based working environments, thus enabling us to better define the baselines of the strength of a human control based on their role and activity. We can then evaluate and analyze the control strengths and, ultimately, determine the mitigations.

In the metaverse, we get the chance to design a world that is mentally and emotionally healthier for our workforce. Capturing the measurements and feeding them into our risk models will transform the way we design systems and bring balance to people, process and technology.