The news that new Home Secretary, Alan Johnson MP, has announced that “holding an identity card should be a personal choice for British citizens” might sound like the death knell for the ID card scheme. However, as always, it is important to read between the lines of political statements. In this case you will discover that the Identity Cards Act 2006 stated quite clearly that the ID cards would not be compulsory unless Parliament voted so later on. The Home Secretary has simply stated that this further vote will not be called for.

Indeed, the voluntary ID cards rollout is now to be sped up, with Londoners expected to get them as early as next year. So has anything changed regarding the privacy and security issues surrounding the scheme?

Now you see it, now you don’t

Certainly nothing has changed as far as creating a National Identity Register (NIR) is concerned. Soon, anyone applying for a new passport will have their fingerprints taken and included on this database along with other personal data. Guy Herbert, general secretary of the non-partisan campaigning group opposed to both the ID card and identity register, NO2ID, says that the ID card scheme is “structured round pseudo-voluntary enrolment” whereby it becomes “impossible not to join if you wish to exercise perfectly ordinary functions in life such as obtaining a passport”.

Herbert considers this typical of the “Kafkaesque logic of the Home Office”, which means that the system can be ‘voluntary’ forever. “If you fail to join the ID register”, Herbert insists “you wouldn’t be refused a passport, you would be held not to have applied for one at all, and voluntarily to have chosen not to be able to travel”.

| "[It is] impossible not to join if you wish to exercise perfectly ordinary functions in life such as obtaining a passport." |

| Guy Herbert |

Alessandro Moretti, executive director of IT security risk management for the UBS investment bank doesn’t know what all the fuss is about. He tells Infosecurity that “as a Swiss and British National I have lived both with and without an ID card scheme, and have come to appreciate the convenience of having a credit-card sized passport in your wallet”.

Moretti can travel throughout Europe (including the UK) with it, hire a car, and use it to offer ID for purchases and banking services. “I only need a passport when travelling to countries that require a Visa or stamped entry”, he says, “the Swiss system is voluntary, but most Swiss carry it which means they have embraced the card and have confidence in the system behind it”.

Getting personal

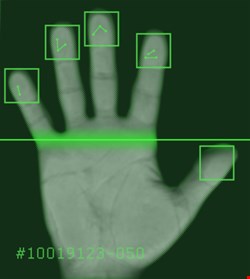

That confidence can stem from the technology used for the ID cards, which means talking biometrics. John Elliott heads up the public sector side of things at IT consultancy Consult Hyperion, and has been advising the UK government on ID cards. “When the UK chose fingerprint”, he tells us “there was no database in the world with 60 million entries that had shown that it can successfully differentiate between all the populous”.

This is one of the reasons why there was interest in iris scanning which claims to be much better at differentiating between people, but Elliott reveals that the government has dropped this “in order to try to reduce costs”. Facial recognition “performs the least well of the three”, but Elliot admits it does have “the comfort factor that humans can recognise faces without machine support”. Facial imaging and fingerprints are the biometrics of choice for most European e-passports.

| "There is an absolute need, within 5-10 years, for a biometric based authentication solution for the general public." |

| Stuart Okin |

Stuart Okin, managing director at Comsec Consulting and a former chief security advisor with Microsoft, makes his position on biometrics quite clear: “there is an absolute need, within 5-10 years, for a biometric based authentication solution for the general public”. He argues that “many nations, most notably the US, will start to insist that biometric checks are done at point of departure and validated on point of entry into the country”. This could require biometrics stored on your passport to be sent before travel and checked against you and the passport upon arrival.

Guy Herbert is not convinced, arguing that fingerprints are “of unknown reliability” and quotes the inventor of iris recognition, Professor John Daugman, as estimating that there would be “1 in 1000 false matches by the time the database contained six million people”.

Herbert is even less convinced by facial imaging systems, claiming they are “close to useless”. In April this year, according to reports, Manchester Airport recalibrated the airport gates facial recognition software to allow people through at a notional 30% match with their passport photo. “The only reason for doing this”, Herbert says “is that otherwise too many false negatives were coming up”.

If you’ve done nothing wrong...

Ultimately though, the argument that faces the anti-ID card lobby will always be that of “if you’ve done nothing wrong, you’ve got nothing to fear”, but John Colley, the European managing director of the Infosecurity membership organisation (ISC)2 and a former head of information security at the Royal Bank of Scotland, calls this a fallacy.

He tells Infosecurity that “the programme goes way beyond the remit of providing proof of identity”, adding “it has become a solution looking for a problem and evolved into a behemoth shaped by far too many political agendas. People should be concerned about their privacy, and their freedom”.

| "The real debate is about the Register or database which will hold everyone's data." |

| Neil Fisher |

Surely someone who has served as a member of the High Level Expert Group on Global Cybersecurity for the Secretary General of the International Telecoms Union would be more accommodating, at least on ID fraud prevention terms? Tom Ilube, chief executive at online identity protection specialists Garlik is also not convinced. He insists that the ID card's impact upon ID fraud would be marginal.

“The vast majority of cybercrime issues affecting individuals would not be impacted one way or the other by the introduction of ID cards”, Ilube says, arguing that “identity thieves are always on the look-out for new forms of identity to target... they will take advantage of the confusion in the early days of any mass roll-out to try and penetrate systems and acquire identities quickly”.

The real debate

Neil Fisher, VP of Global Security Solutions at Unisys, thinks a focus on the ID card itself has always been a distraction, and the “real debate is about the Register or database which will hold everyone’s data”. But didn’t Jacqui Smith announce that there would be no single central database before she resigned as Home Secretary? Well, yes, but what we are actually talking about is information to be held on three existing government databases which resemble a single entity as far as access and search across the network is concerned.

Herbert is not even convinced that the central database for the ID cards was ever a serious proposal. “The last Home Secretary got to announce ‘withdrawal’ of a vague idea purportedly on privacy grounds”, he says, “when in fact she was doing the reverse: pushing forward a huge expansion in surveillance capacity, at the same time as a centralisation of control and diminution of what little oversight there is.”

However, Jamie Cowper, director of marketing at encryption specialists PGP Corporation is in no doubt that “if the appropriate technology, such as data encryption, is implemented then the ID card data should remain totally secure wherever it resides”, and Fisher does indeed say that it has been designed with “resilience and security in mind”.

Phil Neray, VP of strategy at database security experts Guardium, insists that “all computerised systems are at risk from human error, technical failures and abuse”, but he does have suggestions as to how it could be best secured. “In the case of a national ID system”, Neray continues “it’s critical to minimise the risks by implementing robust controls at all layers, but especially at the core database layer”. So, that does mean that real-time monitoring and comprehensive auditing of database access to prevent unauthorised viewing (or tampering) especially by privileged users; strong authentication and identity access management, plus encryption of both data-in-transit and data-at-rest are the very minimum then?

Lack of trust

While security is central to the ID card and NIR technology debate, privacy issues cannot be ignored. Who can ask for access to that NIR data for example? Infosecurity asks LexisNexis professional support lawyer Donald Cran who tells us “the Home Office website doesn’t specify who”. However, it does say that “government agencies and private businesses will be able to check the information held on the national identity register, in order to help them establish the identity of their customers and staff”.

Cran thinks it prudent to assume that data will be available to, among others, “the NHS, DSS, HMRC, the police, local authorities and DVLA in the public sector, and banks, other financial services providers, and retailers in the private sector”.

Unfortunately it would appear that not everyone trusts the government to safeguard the ID card data. Before the MP expenses scandal broke, the results of a survey into government and trust were published. Opinions were mixed when it came to ID cards − 41% in favour and 40% against. However, 72% of the anti lobby said they simply did not feel they could trust the government with their personal data. Of this 72%, a further 93% said they felt this way due to the government’s poor track record with citizen data; 87% thought there was a lack of competence with personal data security in government generally, and 67% didn’t trust the government’s technology expertise.

David Tomlinson, managing director for Data Encryption Systems (DES) which commissioned the survey tells Infosecurity “I would say there are a lot of issues here that the government need to address before it starts asking people to hand over even more information. People have legitimate concerns that need to be heard and acknowledged and the government needs to build up trust again before it can start asking us to have blind faith that these systems will be looked after properly