The continuous exploitation of traditional remote access technologies such as VPNs has been a recurring feature in the past year in cybersecurity. This trend has been growing since the huge surge in VPN adoption (and remote work) during the pandemic, and we all hope 2024 was the climax.

How have VPNs become such a point of weakness? It’s important to remember how urgent the task of spinning up remote access was back in 2020. Organizations were faced with the difficult choice of prioritizing productivity over security, which resulted in too many cases of new technologies being rolled out with insecure default settings or without a solid patching process in place.

In the rush of emergency conditions, the negative effects of an already fast out-dated technology were multiplied, increasing the chances of configuration errors and assembling an expanded technology estate without careful consideration of the ongoing patching and maintenance requirements.

Unfortunately, this trend did not end with the end of the pandemic. Once threat actors understood the potential of this new paradigm, they continued to routinely exploit vulnerabilities and weak default security settings in legacy remote access technologies, particularly VPN concentrators.

As a result, 2024 has seen an unprecedented occurrence of malicious campaigns carried out leveraging software flaws in the very devices that were supposed to provide secure access to internal resources.

It is crucial that organizations understand these attacks and how to secure themselves against the risk of exposed remote access technologies.

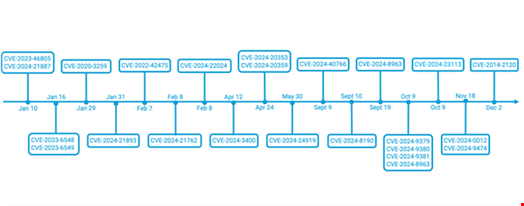

Major Vulnerability Exploitations in 2024

Here are the major exploitations in remote access technologies from the past 12 months.

January 10

In December 2023, state-sponsored threat actors started to exploit CVE-2023-46805 and CVE-2024-21887, authentication bypass and command injection vulnerabilities targeting Ivanti Connect Secure and Policy Secure.

Ivanti first disclosed the vulnerabilities on January 10, 2024. This exploitation was so extreme that the US Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) was forced to issue an emergency directive in response. All agencies were required to immediately implement the mitigation countermeasures published by the vendor, and ironically, CISA would later reveal that it had been breached through the exploitation of the same two vulnerabilities.

January 16

In mid-January, Citrix urged customers to immediately patch Netscaler ADC and Netscaler Gateway appliances exposed online against CVE-2023-6548 and CVE-2023-6549, a code injection and a buffer overflow vulnerability, respectively, actively exploited by threat actors.

January 29

The Akira ransomware group has been found to exploit CVE-2020-3259, an old information disclosure vulnerability targeting Cisco ASA and FTD appliances. This incident is particularly meaningful since this vulnerability was patched in May 2020.

However, the exploitation at scale by the Akira ransomware group was discovered nearly four years later, indicating that many organizations did not apply the countermeasures marked by the vendor.

January 31

Three weeks after the first disclosure, Ivanti patched CVE-2024-21893, a server-side request forgery vulnerability in its Connect Secure, Policy Secure and Neurons products under active exploitation.

February 7

Fortinet was another vendor under pressure in 2024. It all started in February, when it was revealed that the Chinese cyber-espionage group Volt Typhoon breached the Dutch Ministry of Defence in 2023, deploying a novel malware dubbed “Coathanger.” It leveraged CVE-2022-42475, a heap-based buffer overflow vulnerability first exploited in December 2022 and targeting the FortiOS SSL-VPN operating system.

It soon emerged that the campaign was far more extensive than previously thought, resulting in the compromise of at least 20,000 systems worldwide.

February 8

Just one day later, the same vendor disclosed CVE-2024-21762/FG-IR-24-015, an out-of-bounds write vulnerability targeting the SSL-VPN FortiOS Operating System “potentially being exploited in the wild” by threat actors.

On the same day Ivanti warned of CVE-2024-22024, a new authentication bypass vulnerability impacting the Connect Secure, Policy Secure, and ZTA gateways for which exploitation attempts were immediately observed.

April 12

In April, another cybersecurity vendor, Palo Alto Networks, warned that threat actors were exploiting CVE-2024-3400, a critical command injection vulnerability targeting the PAN-OS Operating System, to execute arbitrary code on the vendor’s firewalls in targeted assaults.

April 24

Cisco warned that a state-backed group, tracked as UAT4356 or Storm-1849, had been exploiting CVE-2024-20353 and CVE-2024-20359, zero-day vulnerabilities in the Adaptive Security Appliance (ASA) and Firepower Threat Defense (FTD) firewalls.

This activity was part of a wider campaign tracked as ArcaneDoor, active since November 2023, against government networks worldwide.

May 30

In May it was revealed that threat actors were exploiting CVE-2024-24919, a high-severity information disclosure zero-day vulnerability in the Check Point Remote Access VPN, stealing Active Directory data needed to move laterally through the victims' networks in successful attacks.

September 9

In September, SonicWall warned that a recently fixed improper access control flaw in the SSLVPN SonicOS, tracked as CVE-2024-40766, was "potentially" exploited in attacks. The firm urged admins to apply patches as soon as possible. A day later, security researchers confirmed that the vulnerability was being exploited in ransomware attacks.

September 10

Ivanti confirmed active exploitation of CVE-2024-8190, a high-severity OS command injection vulnerability targeting its Cloud Services Appliance (CSA).

September 19

A few days later, Ivanti warned that threat actors were exploiting CVE-2024-8963, a path traversal vulnerability targeting the Cloud Services Appliance (CSA), chained with CVE-2024-8190, in attacks against “a limited number of customers.”

October 9

Three new Ivanti vulnerabilities, CVE-2024-9379 (SQL Injection), CVE-2024-9380 (OS Command Injection) and CVE-2024-9381 (Path Traversal) targeting the same Cloud Services Appliance were discovered to be under active exploitation chained individually with CVE-2024-8963.

On the same day, CISA added CVE-2024-23113, a format string vulnerability targeting multiple Fortinet products, to its Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog, ordering Federal agencies to patch within three weeks. One important thing to note is that this vulnerability was patched in February 2024, but the widespread exploitation was discovered a few months later.

November 18

Palo Alto Networks released fixes for two vulnerabilities, CVE-2024-0012 and CVE-2024-9474, an authentication bypass and a command injection vulnerability, respectively, in its next-generation firewalls, for which an increasing number of attacks were discovered in November 2024.

December 2

The oldest vulnerability actively exploited in 2024 was CVE-2014-2120, a 10-year-old cross-site scripting (XSS) vulnerability targeting the Cisco Adaptive Security Appliance (ASA).

The vendor detected exploitation attempts in November 2024, and strongly recommended customers to upgrade to a fixed software release. This is an example of how software flaws can be exploited many years after the initial disclosure and remediation.

How to Mitigate the Risk of Exposed Remote Access Technologies

Traditional VPN technologies have a valid alternative in the Zero Trust Network Access paradigm. They allow publishing and segmenting resources located in a local data center or a private or public cloud in a simple way and without direct exposure of remote access concentrators.

They can also open any inbound service in the organization’s network that can be probed by threat actors to look for vulnerabilities and exploit them. The publishers are not directly exposed and only require outbound traffic so the impact of misconfigurations or zero day vulnerabilities is reduced, even in those cases where organizations do not have a robust patching policy.

We’ve seen too many cases where the exploitation of vulnerabilities was possible several months, or even years, after the original disclosure and availability of a security update, simply because the affected organizations did not install the security patches in a timely manner.

Whenever possible, a zero trust approach should be adopted to overcome the limitations of traditional remote access technologies, and reduce the risk of exploitation.