| This article was translated and revised by Patrick Vacek. |

The threat of kleptography has been discussed since the mid-1990s [1], but it was not until recently that it’s received significant attention. This may be in part due to increasingly common discussions about the potential threats from this kind of highly sophisticated attack, but it is more likely due to several recent documented implementations of kleptographic attacks.

These examples show that one of the fundamental aspects of black-box cryptography is also a prime target for intrusion. Hardware security modules (HSMs), smart cards, and Trusted Platform Modules (TPMs) claim to secure cryptographic keys from all external access. However, these devices leave the user with an element of uncertainty: How can the user be sure that the black box is doing exactly what it claims to – and nothing more?

If it’s impossible to externally determine whether a cryptosystem has been manipulated, and the generated output does not appear suspect, one must ultimately place his or her trust in the manufacturer of a cryptosystem to know that no such manipulation has occurred. How can one be sure that the schematics and designs that a manufacturer may provide truly correspond to the finished product? Furthermore, it does not require a conspiracy theorist to imagine the influence that government organizations could have on certain manufacturers. How can we really make sure that we know what is happening inside the black boxes we use?

Kleptography

Kleptography is the "study of stealing information securely and subliminally" [2]. A kleptographic attack is an attack in which a malicious developer uses asymmetric encryption to implement a cryptographic back door. In this way, cryptography is employed against cryptography: the back door in question is not an additional channel of communication to the world outside the cryptosystem, nor does it require the transmission of additional data. The back door is instead embedded directly within the intended communication. Thus, kleptography is a subfield of cryptovirology, the application of cryptography in malware [3,6,11]. However, the target of a kleptographic attack is not just any general form of software, but rather the specific environment of a cryptosystem.

The following example describes a possible kleptographic attack. A black box generates asymmetric key pairs, of which one is a private key and the other public. The private key, which is used in decryption and digital signature generation, should remain exclusively inside the black box to prevent improper usage and duplication. The public key, however, can be freely distributed. As is generally accepted, no one can derive the private key from the public key – or can they?

In fact, such a derivation is indeed possible if the key generation process has been manipulated in a particular fashion. A cryptographic back door could be embedded in the process of manufacturing the cryptosystem, which would then provide an attacker access to the private key without drawing the attention of a third party. This is possible because the generated public keys will not appear conspicuous, nor will any unexpected communication or errors arise while using the cryptographic functionality. The impact is extreme. With a copy of the private key, the attacker can counterfeit signatures and decrypt secret data, even though the cryptographic keys were generated in a sealed black box and no unauthorized access to the contents was permitted.

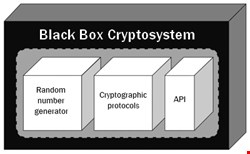

A simplified version of this attack could manipulate the random number generator within the cryptosystem (see Figure 1) such that the key generation process would use a pseudo-random number generator and incorporate a seed known to the attacker, instead of using a truly random function. By knowing the prime numbers generated in the cryptosystem, the attacker could produce a copy of the secret key outside the black box.

A manipulation of this sort could be revealed through reverse engineering, as long as this would not be prevented by a security mechanism, such as those found in dedicated cryptographic hardware. Because the seed of the pseudo-random number generator is fixed within the source code, a reverse engineer could then also calculate the private key outside of the black box. From the attacker's perspective, it is desirable to have exclusive access to the attack mechanism, which would thus no longer be the case. More sophisticated kleptographic attacks can indeed prevent reverse engineers from making this kind of discovery.

SETUP Attack

Kleptography was first discussed in 1996 at the CRYPTO conference by Adam Young and Moti Yung, in which they called attention to numerous opportunities for attacks against the cryptography of black-box systems [1]. They introduced the concept of a "Secretly Embedded Trapdoor with Universal Protection" (SETUP), an attack which they described with respect to RSA key generation.

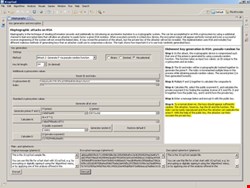

The distinguishing feature of this attack is that it can only be detected through reverse engineering (if at all), and that if found, it still cannot be used by the discoverer. The reverse engineer can only find the public key of the attacker, but not the private key. Because this attack is itself based on asymmetric cryptography, it can be considered ‘secure’ – from the attacker's perspective. This and other kleptographic attacks have been implemented in the e-learning tool JCrypTool (see Figure 2).

Over the years, the SETUP attack has been developed further. The first attacks targeted algorithms based on the difficulty of factoring primes (e.g., RSA), but algorithm attacks relying on the discreet-logarithm problem soon followed. In 2002, a powerful attack against the Diffie-Hellman key exchange algorithm was published [2]. At the 26th Chaos Communication Congress (26C3) in December 2009, Moti Yung alluded to these techniques in his presentation "Yes We Can't!" [5], in which he stressed that kleptography restricts trust in the manufacturer.

Countermeasures

So why has kleptography been slow to garner significant attention, despite hardware cryptosystems being employed precisely where the greatest demands for security exist? After all, HSMs are used specifically to protect particularly sensitive infrastructural keys for businesses in which the potential financial and reputational damage of a successful attack would be extremely high.

Perhaps the fundamental problem is not well-enough recognized, or perhaps users assume that it is in the manufacturer's best interest not to sell manipulated hardware. If the whistle were to be blown on such an incident, the damage could be enough to ruin a company.

There are certainly techniques to counteract kleptography. The European Union requires that security-related industrial hardware must be independently evaluated in two different EU states to achieve maximal transparency over the entire production process.

An even more basic approach is to simply combine hardware from multiple manufacturers into one system. For example, a company could use two smart cards from different and independent manufacturers and then encrypt all data twice, a form of cascading or multiple encryption [6]. In such a case, even if a manufacturer had manipulated the key generation process, it would be unable to decrypt the data, because it would not have the private key of the other smart card. But even with both of these approaches, one can merely reduce the risk. These techniques do not guarantee that manipulation has not occurred, and their increased complexity makes them rather impractical.

Because kleptography requires the use of a subliminal channel to extricate information without detection from a black box, another logical idea is to eliminate all such possible subliminal channels. This line of thought was first pursued in 1984 by Gus Simmons [7] and continued in further publications [8,9], in which random numbers were built into a sort of authentication protocol.

Another technique was introduced in 2002 in which a third party can verify the RSA key generation process [10]. This process is a type of distributed key generation, in which the private key is only known to the black box, thus safeguarding that the key generation was not manipulated and the key cannot be revealed through a kleptographic attack. Other concrete attempts to combat the threat of kleptography have followed, and researchers continue to search for further possibilities.

Looking Forward

Kleptography is richly interesting in terms of cryptography, but in practice it is just one of many threats in a complete system. Rather than manipulate the cryptographic implementation itself, at present it is usually easier for an attacker to assault other components of the system, such as its endpoints. For example, an attacker could use a trojan to capture confidential data from a PC before it was even encrypted by a smart card.

A system is always just as secure as the weakest link in the chain. Kleptography and its defenses will likely become much more significant in the future as security breaches in other components become better recognized and restricted.

It should be considered, however, that in situations that demand the highest security, the expense of implementing countermeasures against kleptography are probably already worth the cost. Even in strongly regulated environments, and even with cross-checking and rigorous testing, the final product can still contain a back door or may be vulnerable to some form of intrusion. After all, it is not necessarily the manufacturer that may construct a back door to a cryptosystem.

|

For the sake of comparison and clarification, the following demonstrates the process of normal RSA key generation with 2048-bit keys:

This process produces the public key (n, e) and the private key (d). The encryption and decryption of a message m with RSA is carried out via exponentiation:

The kleptographic RSA key generation process (presented here in a simplified version from [4]) is modified and uses the public key of the attacker's own RSA key pair (N, E). Note that the attacker's key is half as long (in this case, 1024 bits) as the keys under attack.

The result is again a public key (n, e) and a private key (d). The discovery of the private key is only possible with possession of the public key (n, e) created by the kleptographic RSA key generation as well as the private key of the attacker (D):

As a result, the attacker acquires the private key (d) of the victim. |

Professor Bernhard Esslinger teaches IT security and cryptography at the University of Siegen and leads the open-source CrypTool project.

Patrick Vacek is a software developer for Exegy, Inc. in St. Louis and is also a contributor to the CrypTool project.

| This article was originally published by <kes> – The Information Security Journal and has been translated from the original German |

References

[1] A. Young, M. Yung, The Dark Side of Black-Box Cryptography, or: Should we trust Capstone?, in: N. Koblitz (Ed.), Advances in Cryptology – Crypto ’96, LNCS 1109, Springer, 1996, ISBN 978-3-540-

61512-5

[2] A. Young, M. Yung, Kleptography: Using Cryptography Against Cryptography, in: W. Fumy (Ed.), Advances in Cryptology – Eurocrypt ’97, LNCS 1233, Springer, 1997, ISBN 978-3-540-62975-7

[3] A. Young, M. Yung, Cryptovirology FAQ, Version 1.31, http://www.cryptovirology.com/cryptovfiles/cryptovirologyfaqver1.html

[4] M. Yung, Kleptography: The Outsider Inside Your Crypto Devices, and its Trust Implications, DIMACS Workshop on Theft in E-Commerce: Content, Identity, and Service, 2005, Powerpoint Presentation: http://dimacs.rutgers.edu/Workshops/Intellectual/slides/yung.ppt

[5] M. Yung, Yes We Can’t, 26th Chaos Communication Congress, 2009, MPEG-4 video recording: http://events.ccc.de/congress/2009/Fahrplan/events/3702.en.html

[6] A. Young, M. Yung, Malicious Cryptography: Exposing Cryptovirology, John Wiley & Sons, 2004,

ISBN 978-0-7645-4975-5

[7] G. J. Simmons, The Prisoners' Problem and the Subliminal Channel, in: D. Chaum (Ed.), Proceedings of Crypto ’83, Plenum Press, 1984, ISBN 978-0-306-41637-8

[8] G. J. Simmons, The Subliminal Channel and Digital Signatures, in: T. Beth, N. Cot, I. Ingemarsson

(Eds.), Proceedings of Eurocrypt ’84, LNCS 209, Springer-Verlag, 1985, ISBN 978-3-540-16076-2

[9] Y. Desmedt, C. Goutier, S. Bengio, Special Uses and Abuses of the Fiat-Shamir Passport Protocol, in: C. Pomerance (Ed.), Proceedings of Crypto ’87, LNCS 293, Springer-Verlag, 1988, ISBN 978-3-540-18796-7

[10] A. Juels, J. Guajardo, RSA Key Generation with Verifiable Randomness, in: D. Naccache, P. Pallier (Eds.), Public Key Cryptography: 4th International Workshop on Practice and Theory in Public Key Cryptosystems, Springer-Verlag, 2002, ISBN 978-3-540-43168-8

[11] A. Yung, M. Young, Towards a Book on Advances in Cryptovirology, Selected Chapters as PDF, www.cryptovirology.com/cryptovfiles/newbook.html